Experimenting with HTTP services - UrlEcho and UrlReq

Introduction

UrlEcho and UrlReq are two HTTP services I built a few years ago when I started learning about the Web’s architecture. The services are fairly generic and might be useful to other people experimenting, testing and debugging Web-based systems. They are hosted on AppEngine and free to use.

Both services receive an HTTP request which contains a definition of another HTTP message in the URL of the received request, and then do something with that message.

The UrlEcho service

Requests to the UrlEcho service should contain the definition of a HTTP response message in the URL (i.e. the status, headers and body of the response). Upon receiving the request, UrlEcho responds to the requestor with the HTTP response defined in the URL of the request. Here’s an example request URL (clickable link here):

http://urlecho.appspot.com/echo?status=200&Content-Type=text%2Fhtml&body=Hello%20world!

and the corresponding HTTP response which is defined in the URL and will be echoed back to the requestor:

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

Content-Type: text/html

Hello World!

As shown in the example, the API for the service is simple (split into multiple lines for clarity):

http://urlecho.appspot.com/echo

?status=<HTTP_STATUS>

&<HEADER1_NAME>=<HEADER1_VALUE>

&<HEADER2_NAME>=<HEADER2_VALUE>

&body=<BODY_STRING>

where the strings for header names and values, and for the body must be URL encoded.

The UrlReq service

On the other hand, requests to the UrlReq service should contain the definition of another HTTP request message in the URL (i.e. the method, url, headers and body of the request). Upon receiving the request, UrlReq performs the request defined in the URL, and forwards the received response back to the requestor. Here’s an example request URL for requesting HTML rendering of Markdown input using GitHub’s API (clickable link here):

http://urlreq.appspot.com/req?method=POST&url=https%3A%2F%2Fapi.github.com%2Fmarkdown%2Fraw&

Content-Type=text%2Fplain&body=**Hello**%20_World_!

the corresponding HTTP request hosted in the URL:

POST /markdown/raw

Host: api.github.com

Content-Type: text/plain

**Hello** _World_!

and the response received from the service:

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

Content-Type: text/html;charset=utf-8

...

<p><strong>Hello</strong> <em>World</em>!</p>

As shown in the example, the API for the service is simple (split into multiple lines for clarity):

http://urlreq.appspot.com/req

?method=<HTTP_METHOD>

&url=<TARGET_URL>

&<HEADER1_NAME>=<HEADER1_VALUE>

&<HEADER2_NAME>=<HEADER2_VALUE>

&body=<BODY_STRING>

where the strings for header names and values, for the target URL, and for the body must be URL encoded.

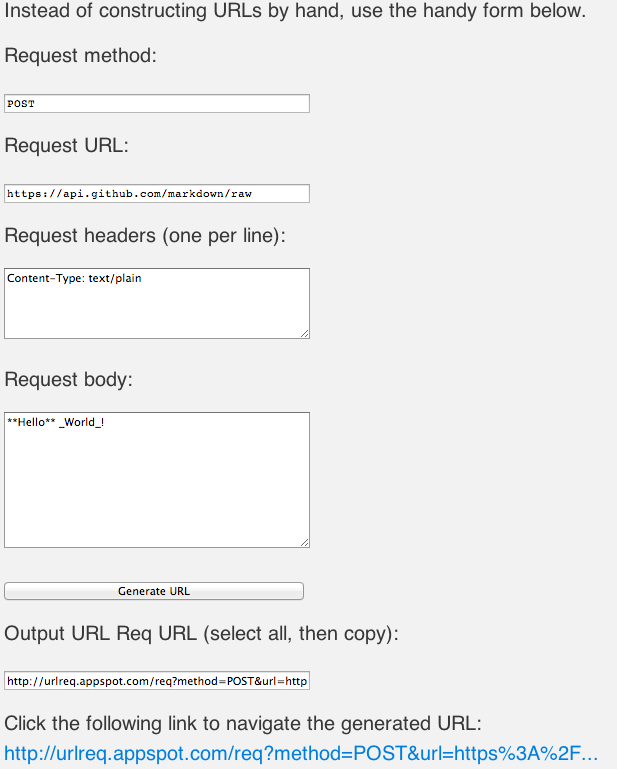

URL builders and debug mode

To make the construction of such URLs easier, simple URL builder forms are available for both services: UrlEcho URL builder and UrlReq URL builder (scroll down when you get to the project page).

Also, both services have support for debug mode by appending &debugMode=1 to the end of the URLs.

When in debug mode, the services return a text/plain version of the HTTP response that would be returned if the service was not in debug mode.

So, it’s basically a text log output of the intended HTTP response.

Why build these services?

In a way, both services change/break the default way of using HTTP – the URL is used for more than identifying a resource and the services are just stateless shells that either echo requests or responses. They could be thought of a special kind of HTTP intermediaries.

UrlEcho permits the requestor to completely define the response it wants to receive, thus giving it the ability to “host” static HTTP resources within URLs themselves. Why is this cool/useful?

- You don’t need a Web server to host a simple resource – you just construct a URL and you’re set to go.

- Since resources are cheap to create and throw away, you can create as many URLs as you want, when you want them.

- This is especially useful for testing – you don’t want to configure many server-side resources to return hard-coded responses in order to test correct handling of that response. For example, imagine you need many simple iframes to test a JavaScript library, and you don’t want to modify the server hosting the iframes each time you add or change tests. Since you already know what the responses will be, why not define them in the requests and have a simpler testing process? It makes tests easier to maintain (no need to modify the server) and understand (due to response visibility in the tests).

UrlEcho lets the requestor to wrap any HTTP request (any method, with headers and body) into a simple GET request with only an URL defined. Why is this cool/useful?

- You can make any HTTP request in situations where only a simple GET is possible, or where you can only define just the URL. For example, most systems that provide Web hook callbacks only let you define the callback URL only (not the method, headers or body structure).

In general, the reasons behind using URLs to “host” HTTP messages (versus choosing headers or the body) is that it has the widest possible applicability.

The URL is often the only thing you can define for a request – e.g. in <a> and <iframe> HTML elements, and when defining Web hook callbacks.

You can’t set HTTP headers or the body in such situations, the URL is all you have access to.

The example I gave above for UrlReq, the one for rendering Markdown text to HTML using GitHub’s API – isn’t it cool how you can give a simple link to someone, that makes a POST request behind the scenes?

It is.

Note also that the services don’t respond just to HTTP GET requests, but also to HEAD, POST, PUT, DELETE and OPTIONS requests. This means that, for example, you can make an HTTP DELETE request to UrlReq and make it do an HTTP POST or HTTP PUT request in the background, just by playing with the URL.

Other nits and bits

The main issue with using URLs for passing data is that URLs have limited length. You just can’t put 10 MB in there.

Long, ugly URLs make you go Meh.? Just use an URL shortening service on the long URL, like so: http://goo.gl/UOQPy.

A few notes about security-related issues. After successfully using UrlEcho for over a year, I noticed it stopped working for me in Chrome. Turns out, using UrlEcho for echoing back HTML documents with JavaScript scripts makes browsers think there is an XSS attack happening. For example, the following URL (clickable link here):

http://urlecho.appspot.com/echo?status=200&Content-Type=text%2Fhtml&body=%3Chtml%3E%0A%20%20%3C

head%3E%0A%20%20%3C%2Fhead%3E%0A%20%20%3Cbody%3E%0A%20%20%20%20%3Cscript%3E%0A%20%20%20%20%20%20

console.log(%22Hello%20world!%22)%3B%0A%20%20%20%20%3C%2Fscript%3E%0A%20%20%3C%2Fbody%3E%0A%3C%2F

head%3E

echoes back a simple HTML document with a console.log("Hello world!") script.

However, the script will not get executed and Chrome will log the following error to the console: “Refused to execute a JavaScript script. Source code of script found within request.”

I suppose security hackers can find a way to trick Chrome and get around this, by tweaking the request content.

But, this is something you should be aware of.

Finally, cross-origin calls to both services are enabled via CORS headers, both services are accessible over HTTPS, and the UrlEcho service responds on arbitrary subdomains, e.g. http://mysubdomain.urlecho.appspot.com/echo?....

Conclusion

More information about UrlEcho and UrlReq is available on their Web sites. Let me know if you like the services, think they’re an abomination of the Web, or have any other cool ideas for HTTP services.

As for me, I really learned to appreciate nice and simple HTTP services with generic applicability. There is a nice list of other such services in my blog post The Web Engineer’s online toolbox.

Comments